TAVUSH: the first step is the hardest – Samvel Meliksetyan

The delimitation and demarcation process for the ‘four villages’ section of the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan began in March-April 2024. The transfer to Azerbaijan of territory previously controlled by Armenia was completed in late July. This was accompanied by the erection of a concrete wall near the village of Kirants, bringing profound changes to life there and to the status of the village. New bypass roads and border infrastructure were also constructed. For the first time in the history of Armenian-Azerbaijani relations a 12.7-km section of state border was established – with border guards stationed along it instead of minefields and trenches on either side. Since then, the peace process and further work on the legal framework and principles of the border delimitation and demarcation have stalled, raising concerns that this decisive step could end up being an anomaly in the logic of the ongoing conflict.

There is now a window of opportunity to seek both to better understand the details of the process that took place in Tavush and to use it to identify the shortcomings and to propose better solutions and models for the negotiation process going forward. That is the aim of this article and we strongly believe that it is in the objective interests of the people of both countries.

WHAT HAPPENED

On 9 March 2024, the office of Azerbaijani Deputy Prime Minister Shahin Mustafayev issued a demand for the “immediate liberation” of four non-exclave villages in the Qazax district. Despite this initial tone of ultimatum, it marked the beginning of the process that resulted in the first example of a delimitation and demarcation agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan – on a 12.7-km section of the border shared by the two countries and based on the “legally established inter-republic border which existed within the Soviet Union at the time of its dissolution”. The process concluded with the transfer to Azerbaijan of four non-exclave villages in the Qazax district (Baghanis Ayrim, Ashaghi Askipara, Kheyrimli and Gizilhajili) which were under the full or partial control of Armenia in the first half of 1992.

It should be noted that official Armenian sources have tended to talk about ‘two-and-a-half’ rather than four villages, which is strictly speaking more accurate. Two villages were fully under Armenian control (Baghanis Ayrim and Kheyrimli) and the presence of Armenian military positions on the outskirts of the villages of Ashaghi Askipara and Gizilhajili meant the Azerbaijani side couldn’t enter their territory unless the bases were withdrawn. A demand for the return of the villages in the Qazax district was also included in the original text of the tripartite agreement of 9/10 November 2020, but it was removed due to objections from the Armenian side. The groups of villages were initially divided into exclaves and non-exclaves. (Consideration of the exclaves would also involve deciding the fate of the Armenian village of Artsvashen which, at the beginning of the Karabakh conflict, had a population almost twice that of the four Azerbaijani villages in the Azerbaijani enclaves combined). There were elements of compromise, since restoring the borders with enclaves but without addressing and resolving key issues of Armenian-Azerbaijani relations would involve risks for both sides and could turn the potential inhabitants of these territories into hostages of the current political process.

Following the statement on 18 March, the Armenian Prime Minister, Nikol Pashinyan, visited the Armenian border villages in this area (Baghanis, Voskepar, Kirants and Berkaber). During his visit he said a refusal to accede to Baku’s demands would be linked to an inevitable escalation of hostilities by the Azerbaijani side. Pashinyan’s words were perceived as intimidation towards the residents of the Armenian border villages and a unilateral ceding of territory (even the very fact that these villages belonged to Azerbaijan was often disputed) and led to a wave of critical reaction in Armenian media and society. This marked the beginning of an acute internal political crisis and significant social unrest in Armenia from November 2020. The resentment and apprehension were particularly evident in two of the villages – Voskepar and Kirants. A return to the Soviet-era borders would mean these villages would lose homes, farm and other buildings, land holdings and communications links.

In an article from 6 March 2024 we described the situation in this area in detail, together with possible routes out of the crisis. The main argument was that if the Azerbaijani side wasn’t prepared to return the area of territory to the north of the Joghaz (Berkaber) reservoir to Armenia, then it would be necessary to separate the territory of the Azerbaijani villages which were to be returned to Azerbaijan from territory where there were no settlements but which were important to each side in terms of communications. At the meeting with the Armenian Prime Minister on 18 March 2024, residents of the village of Voskepar put forward a similar proposal: return the territory of the village of Ashaghi Askipara proper to Azerbaijan, but leave the ‘Voskepar Triangle’ to the south of the village under Armenian control (see map).

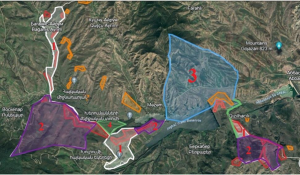

A similar solution was devised by the delimitation and demarcation commissions which, in a joint statement on 19 April 2024, made a distinction between areas where there were Azerbaijani settlements and areas that were uninhabited (the future of which will be decided at the final delimitation stage). Thus, in addition to the ‘Voskepar Triangle’, an area of Azerbaijani territory to the north-east of the village of Kheyrimli remained under Armenian control, as well as most of the Armenian positions near the village of Gizilhajili (see map below). This solution also allowed Azerbaijan to retain the Joghaz ledge (marked 3 on the map).

Map 1

Solution in the Voskepar (Askipara) area based on the 19 April 2024 statement

1) Outlined in white (1): immediate territories of the villages of Qazax district under Armenian control which are being returned to Azerbaijan and where the delimitation is taking place

2) Outlined in purple (2): territory of Qazax district under Armenian control which is to remain on the Armenian side until the final delimitation of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border

3) Outlined in blue (3): territory of Armenia to the north of the Joghaz Reservoir (approx. 7 km²), which is to remain under Azerbaijani control until the final delimitation.

4) Territory of Armenia (4) to the north of the village of Kirants (neutral zone) which, as a result of this process, was again transferred to Armenian control.

Shapes outlined in orange – Azerbaijani military positions in the delimitation zone

Shapes outlined in red – Armenian military positions in the delimitation zone

Important outcomes from the joint statement of 19 April 2024 include:

1) An indication that the border will correspond to the “legally established inter-republic border which existed within the Soviet Union at the time of its dissolution”. It was later confirmed that this would involve delineating a border between the two republics in accordance with the Soviet General Staff map made in 1976 and revised in 1979. As outlined in our previous article, at the time of the invasion of Armenian territory in May 2021 in the area around Lake Sevlich (Ishigli-Garagyol), the Azerbaijani side used false maps with distorted border contours. In light of this, the selection and agreement (and documentation) of a very specific cartographic framework represents an important achievement.

2) A reference to the Alma-Ata Declaration of 21 December 1991. This was the document that formalised the dissolution of the USSR and the principle of the inviolability of the borders and the territorial integrity of the republics which formed the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). This point had been included in statements made by the leaders of the two countries since late 2022, but was recognised here for the first time as a guiding principle in the practical delimitation of specific sections of the border. The joint statement also noted that this provision from the Alma-Ata Declaration would be one of the fundamental principles of the Regulation on the joint activities of the commissions of the two countries.

3) The indication of a deadline of 1 July by which the Regulation on the joint activities of the commissions of the two countries was to be completed, following the approval of which the priorities should be set for the new border delimitation process, including enclaves and exclaves.

This last point was not achieved within the stated time limit and, as the deadline passed, both sides issued statements to the effect that the negotiations over the document were continuing constructively and would come to a positive conclusion very soon. Despite the optimistic tone of these pronouncements, during the course of July it became clear that the Azerbaijani side was in no hurry and, in fact, its rhetoric had hardened. We believe that a recognition of the general principles for the settlement of relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan and the adoption of the amended Regulations should form the basis of a ‘framework agreement’, which appears to be the most likely alternative to the somewhat improbable prospect of a comprehensive peace treaty. Whether or not this ‘framework agreement’ will actually be signed by the end of the year remains an open question.

It’s notable that the 19 April statement came almost immediately after the news of the withdrawal of Russian peace-keeping forces from Nagorny Karabakh. Furthermore, after Nikol Pashinyan’s visit to Moscow on 8 May the decision was taken to remove Russian observation posts from the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan (including the one in the delimitation zone north of the village of Voskepar).

Returning to the process which followed the joint statement, we can say that, strictly speaking, there has been no new delimitation (i.e. negotiations to define and adjust the line of the border on the map), although an agreement was reached to restore the 1976 administrative border, meaning the Soviet delimitation of the administrative border.

However, the transition from the delimitation to the demarcation phase revealed a series of problems on the ground, particularly in the area around the village of Kirants. On 1 May, in an interview with Armenia Public Television, Prime Minister Pashinyan confirmed that the process was ongoing to “reinstate the administrative border” from the time of the dissolution of the USSR and that only three or four of the 11 disputed points in relation to the area around the village of Kirants were still to be resolved. These related to the bridge and entry to the village from that side. Later, on 7 May, Kamo Shahinyan, head of the village of Kirants, said in an interview with Armenian media that the process of demarcation was progressing favourably for the Armenian side and that talks were ongoing to define and resolve problems on three points, although the process had stalled. These pronouncements provided indirect evidence of the fact that, when faced with issues around village infrastructure and communications during the demarcation phase, the parties were demonstrating a willingness to take into account the interests of the people living in the border zone. This approach was one of the cornerstones of the OSCE recommendations on delimitation and demarcation.

Nevertheless, further news from Kirants and growing discontent among the villagers suggested that no compromise had been reached on the ‘three points’ and later, as reported by the Armenian Prime Minister during a meeting of his government, it was ultimately decided that “the border goes where it goes”. This means the demarcation would rigidly follow the Soviet map, without any corrections to the border line or any adjustments for local factors. The 9th meeting of the delimitation commissions on 15 May 2024 definitively established this principle and culminated in a protocol finalising the delimitation and demarcation of the Baghanis-Voskepar / Baghanis Ayrim-Ashaghi Askipara; Kirants / Kheyrimli; and Berkaber / Gizilhajili sections.

DELIMITATION OR BORDERISATION?

This important question arose right from the beginning of the process described here. Although there are popular views (including within Armenian domestic political discourse) about the existence in international law of special norms and requirements in relation to delimitation, there are no unified guidelines for the implementation of such measures. The OSCE handbook, published in 2017, is often referenced as a regulatory document on the rules of delimitation and demarcation. However, it is purely advisory and provides recommendations based on the successful example of delimitation and demarcation between Belarus and Lithuania as a model for other states of the former USSR and Eastern Europe.

Agreements on border delimitation in the newly emerged states in the region cite the general principles of international law enshrined in the UN Charter and the Helsinki Final Act. For the CIS states the important documents which refer to these same principles are the Alma-Ata Declaration (1991), the CIS Charter (1993) and the Declaration on respect for sovereignty, territorial integrity and immunity of borders of the State Parties of the Commonwealth of Independent States (1994). These fundamental documents include the principles of non-use of force or threat of force (as well as the peaceful resolution of international disputes), the inviolability of borders, and the recognition of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of states. Any agreements between parties which are reached voluntarily and do not contradict these legal instruments, including in relation to border changes or clarifications, are deemed acceptable.

The OSCE handbook provides a non-mandatory but optimal model for situations where states face challenges of:

а) divided settlements;

b) energy, transport, irrigation and other communication lines that cross a border;

c) economic entities located along or across a border (land holdings, forest, mineral deposits etc.);

d) the presence of enclaves / exclaves.

Consideration of mutual interests is key in relation to preserving connectivity, established land-use practices, and the integrity of settlements and their infrastructure. However, this approach towards delimitation is not universal. In the absence of agreement between two parties, the basic principles may be different if the sides are not willing to reach an understanding about adjusting and optimising each section of the border concerned. Delimitation agreements may also include general provisions on an acceptable range for border adjustments on the ground to resolve local issues that may arise. For example, in the delimitation agreement between the Republic of Macedonia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (2001) the permitted variation between demarcation on the ground and the text description of the border (i.e. the line of delimitation) was 150 m.

There are numerous examples from the mid-20th century, such as the Soviet-Polish delimitation and demarcation process, where the interests of populations living in border regions were not taken into account and villages that were divided during the demarcation process were evacuated. This happened in particular when there were strict rules governing the width of border strips and how they were to be managed. In the case of the delimitation process for the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, applying the principle of “the border goes where it goes” (based on a series of maps produced by the Soviet General Staff in 1976) will lead to multiple issues for local residents. Yet this approach does, in fact, comply formally with customary practices.

For this reason it is difficult to accept the characterisation of what has happened as an example of borderisation, i.e. the establishment of the line of contact or occupation as the official border even if one of the parties disagrees. The term borderisation became prevalent after the process to ‘define’ and establish the ‘border’ between South Ossetia and Georgia, when the Russian / Ossetian side unilaterally installed border posts, barbed wire and other border infrastructure. Through this process a ‘border’ was established with Georgia and border controls were introduced for the divided Georgian settlements. However, the process was not recognised by the Georgian side. An important difference in the case we are considering here is that Armenia and Azerbaijan were formally engaged in a delimitation/demarcation process, following all the official procedures and mutual agreements, with a specific legal framework and accepted cartography, and the two parties were internationally recognised as having equal legal status (i.e. they were recognised states).

An example of borderisation can be found in the events of early 2021 on the section of the border between Goris and Kapan when, without any formal agreement, the Armenian side ceded territory to Azerbaijan. Although it had previously formally been part of Soviet Azerbaijan, the territory was transferred under coercive pressure, was not enshrined in any formal agreement with a legal basis and was accompanied by violations.

With regard to the delimitation process undertaken by Armenia and Azerbaijan for the Tavush border section, there were a number of specific issues which were not typical of other post-Soviet precedents and caused significant problems. Firstly, no post-Soviet state has embarked on a delimitation process in circumstances where the old administrative border had been significantly violated in multiple places in the course of armed conflict and where some settlements had ceased to exist.

Secondly, the process took place against a background of persistent and long-standing conflict, which had been transformed not through a process of de-escalation and negotiation, but through war, the defeat of the Armenian side and an absence of international arbitrators with an interest in a definitive settlement. This factor was determined not only by Baku’s interests in the return of the villages, but also by a wish to demonstrate the effectiveness of a bilateral format, which explains the willingness of the Azerbaijani side to make certain compromises. At the same time, the public rhetoric from Baku was rather dry and primarily emphasised the gains made by Azerbaijan during the process. This highlights a characteristic feature of Azerbaijan’s approach at the official level which involves not acknowledging any concessions it makes. In contrast, in the Armenian public space news about concessions made by Yerevan is met with pain and anger.

The presence of domestic political opposition is self-evident, since the Armenia authorities entered into the ‘Tavush process’ under pressure from the Azerbaijani side. Armenia didn’t set its own agenda and was compelled to accommodate Baku’s demands and this amplified the troubled reaction in Armenia. Furthermore, unlike the Azerbaijani leadership, the government in Yerevan didn’t have a monopoly on communicating its view of events. Despite the efforts of the Prime Minister and his team to present the process as the start of mutual recognition of each other’s borders by the two countries, which should reduce the risk of future escalations and pave the way for the delimitation of the whole border, the opposition, the media and a significant proportion of experts in the field interpreted what happened as unilateral concessions with no guarantee of a corresponding response from the other side.

One of the main contentions of Pashinyan’s opponents was the lack of commitment from Baku to liberate Armenian territory seized during the 1990s and between 2021 and 2022. The process was also perceived as having destroyed the well-equipped line of defence which had been established in the 1990s in this area. There was therefore a fear that, during the next stages, the Azerbaijani side would impose new conditions, taking advantage of the weakness of Armenia’s defensive positions. The atmosphere of this intense discourse gave rise to many contradictory messages, fake news, propaganda and leaks that in no way helped to create a realistic picture of the actual process.

Amidst the internal controversy in Armenia there are positive aspects, such as the efforts of the authorities to establish multiple channels of communication and to include community leaders in the delimitation commission working group, thereby leading to better representation of the interests of border communities. However, the lack of established mechanisms for this public participation has led to mixed results. The premature disclosure of details of the process on the border section near Kirants fed political speculation which in turn had a negative impact on work to resolve issues around the bridge and a number of facilities in the village. Constructive agreement was hindered by a series of public pronouncements from the Armenian side, presenting the process in an exclusively positive light for Armenia.

Another problem linked to the political landscape was that it dictated the selection of the simplest and most comprehensible principle to affirm Armenia’s territorial integrity – a strict adherence to the Soviet-era administrative border. The recognition of this border by Azerbaijan, whose official representatives frequently used the phrase “the provisional border with Armenia”, was perceived by officials in Yerevan as a major political achievement. In contrast, the costs, in terms of the loss of cross-border infrastructure which had evolved through actual use practices, were viewed as being of secondary importance. For the same reasons, details about the optimisation of the border and how it was adjusted with consideration for local needs were also largely overlooked.

It is also worth mentioning here the questionable benefit of references by the authorities to the notion of 29,743 km², since the delimitation and demarcation process does not always involve the strict preservation of a fixed area of territory. When the optimised border principle is applied, the process may lead to neighbouring countries gaining or losing a certain amount of territory.

For example, during the delimitation process between Russia and China, Russia lost a number of islands in the Amur River, moved the border in Azerbaijan’s favour in the region of the Samur River hydro scheme and ceded exclaves (Khrakh-Uba and Uryan-Uba). After lengthy negotiations, Ukraine and Belarus worked out a way to deal with transfluvial areas, departing from a strict adherence to ‘kilometre-counting’. Determining the parameters of border alignment when dealing with bodies of water (the centreline of a river, thalweg etc.) and other features, as well as natural processes where the situation on the ground changes and no longer corresponds to the map, can lead to territorial gains and losses which may not always be the same for both parties, although as a rule the differences are insignificant.

In other words the political and propaganda element during the delimitation in the ‘four villages’ area played a generally negative role and raised questions about the effectiveness of continuing the process on further sections of the border.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND RESULTS ‘ON THE GROUND’

As was repeatedly noted by a range of authors at the beginning of the ‘four villages’ demarcation process, in 1992-93 the Armenian side, seeking to preserve its communications and ensure the security of the village of Berkaber, took control of a section of the road between Kirants and Baghanis and – wholly or in part – the Azerbaijani villages located alongside it (Kheyrimli, Ashaghi Askipara and Baghanis Ayrim). The occupation of the heights to the east of the village of Berkaber in 1993 also led to the departure of the residents of the Azerbaijani village of Gizilhajili, situated next to the hill. As a result of fortification works in the years that followed and an increased Armenian military presence in these areas, 8.3-8.5 km² of the Qazax district of Azerbaijan came under Armenian control. For its part, Azerbaijan occupied the whole of the protruding area of Armenian territory to the north of the Joghaz reservoir, an area of around 6.8-7km², which secured the transport link between this area and ‘mainland’ Azerbaijan.

To understand the complexity of the picture here, it’s important to know that in 1991 the villages of Baghanis Ayrim, Gushchu Ayrim, Mazam, Ashaghi Askipara and Kheyrimli were located in a so-called pene-enclave, that is they were on the territory of a state (Azerbaijan) which could only be reached through the territory of a neighbouring state (Armenia), since the direct overland connection between this area and Azerbaijan went through the mountains (Mount Odundagh). What’s more, Kheyrimli was in a double pene-enclave, because in order to reach it by road, you would have to go from the pene-enclave of Askipara into Armenia and only then was it possible to get to the village.

In addition, after 1992-93 around 25 ha of Armenian territory to the north of the village of Kirants was located between Armenian and Azerbaijani positions. Overall, the neutral zone in this area between the Armenian and Azerbaijani trenches accounted for around 4.5-5 km². This is why the statement from the office of Shahin Mustafayev noted that, as a result of the return of the four villages, Azerbaijan had gained 6.5 km², while Armenia had only lost an area of 2.6-2.8 km². Azerbaijan only arrived at these figures by also taking into account the area that had formerly functioned as the neutral zone between the two positions.

Map 2 The area around Voskepar before the beginning of the delimitation process

1) Yellow – territory of Azerbaijan under the control of Armenian armed forces.

2) Red – territory of Armenia under the control of Azerbaijani armed forces.

3) Pink – neutral zone within Armenian territory.

4) Grey – neutral zone within Azerbaijani territory.

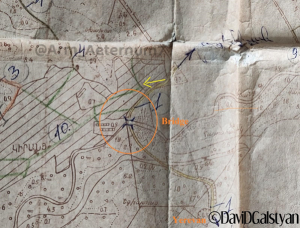

Before the beginning of the Karabakh conflict, the relationships between these settlements and the infrastructure connecting them was typical of many areas on the borders between the republics of the USSR. The example of Kirants or the Azerbaijani villages of Baghanis Ayrim and Ashaghi Askipara is therefore quite typical. The bridge linking the district centre of Ijevan with the village of Kirants was built on the administrative territory of the Azerbaijani Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), but by Armenian construction workers and paid for from the budget of the Armenian SSR. Furthermore, during Soviet times, the villagers were engaged in economic activities in the adjacent area, sometimes across the administrative boundary. This was reflected in the land-use maps published by the relevant agencies, such as the State Land Institute of the Armenian SSR, see map below.

Land-use map of the village of Kirants. The area around the bridge and below is shown as part of the village (published by journalist David Galstyan).

It was a common phenomenon in the USSR for there to be contradictions between land-use maps, published by the relevant Soviet agencies, and reference maps showing the administrative boundaries (including those produced by the General Staff). The complexity of the situation is mentioned in the OSCE handbook. However, it was the reference maps rather than the land-use maps that reflected the administrative border. This situation was a factor in the delimitation and demarcation of almost all the Soviet republics. The alignment of two realities is an important task for ‘good delimitation’ and one of the most challenging. For example, when embarking on the delimitation of the border between Ukraine and Belarus, the head of the Ukrainian commission received the following instruction: “When defining the line of the border, be guided by the administrative border line while taking into account the borders according to actual land-use”.

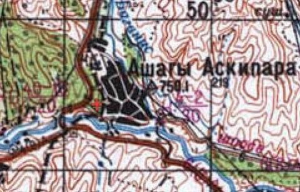

Thus part of the Azerbaijani village of Baghanis Ayrim was located on the administrative territory of the Armenian SSR. The expansion of another Azerbaijani village, Ashaghi Askipara, meant that by the 1970s and 1980s new houses were also being built towards and even across the Armenian border.

The border between the Armenian SSR and the Azerbaijani SSR at the section near the villages of Baghanis and Voskepar according to the USSR General Staff map of 1990. It can be seen that some of the buildings in the villages of Baghanis Ayrim and Ashaghi Askipara are to the west of the border line (dotted red line), i.e. on the territory of Armenia.

In the latter case this led to acute conflict with the population of Armenian Voskepar. Meanwhile, the Armenian side, seeking to prevent the ‘expansion’ of the Azerbaijani village, built new houses along the border, although they were never used due to the outbreak of the Karabakh conflict.

One of the Armenian houses built in the mid-1980s in the village of Voskepar. Beyond the church (on the left) the remains of an Azerbaijani house are visible. Photo Tatul Hakobyan.

The Armenian-Azerbaijani border commission’s decision of 12 January 1988 also included a point about the recognition of such border infringements and adjustments in line with land-use practice, with compensation for land lost, based on the equal area principle. Therefore, in accordance with this decision, state farms in the Armenian villages of Baghanis and Voskepar received by way of compensation land of an equal area to that which was lost as a result of the expansion of the village of Ashaghi Askipara at the expense of administrative territory of the Armenian SSR.

The changes to the border in the area around Ashaghi Askipara (near the 6th-7th-century church of St Astvatsatsin) can be seen by comparing the Soviet General Staff map from 1976 with the map from 1990. On the 1976 General Staff map the distance between the church and the border is just over 100 m, while on the map from 1990 it is around 22 m.

As already explained, it was decided to base the delineation of the administrative border on the Soviet General Staff map from 1976, reviewed in 1979. Based on this map and the accompanying description, as well as the Soviet General Staff map from 1990, the village of Baghanis Ayrim was divided by the river of the same name into a larger part (within the borders of the Azerbaijani SSR) and a smaller part (within the borders of the Armenian SSR). Near the village of Kirants the contours of the border appear to correspond, as far as it’s possible to judge, given the different scales of the maps. The only difference in this area concerns the line of the border near the church of St Astvatsatsin in the village of Ashaghi Askipara. Since the delimitation line strictly follows the line of the 1976 administrative border, the semi-ruined village which in 1988-1991 occupied part of the territory of the Armenian SSR, has also been divided between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Azerbaijanis who return to their village will therefore find a reality on the ground that is different from the situation in the late 1980s.

The situation in the area around Kirants was the most challenging. Here adherence to the chosen approach generated bitter resentment in the villagers when they encountered state border controls for the first time in their lives and lost 54 buildings, including two dwellings, as well as other buildings and land which they had been able to continue to use, even when they were on the territory of the Azerbaijani SSR.

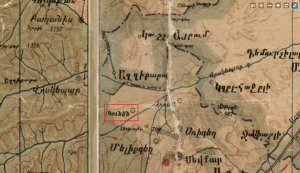

The complex pattern of land-use in the border area around Kirants and the small neighbouring Azerbaijani village of Kheyrimli (which was isolated from the other Azerbaijani villages in this area) was the source of numerous problems from the 1920s onwards. As a result, the border issue in this area was discussed repeatedly by the commissions established by the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and in 1929 it was decided that the two villages should be united (at that time Kirants was known as Kunen) to form a single soviet entity and transferred either to the Dilijan district in Armenia or the Qazax district in Azerbaijan. Judging by the most detailed and accurate map of Soviet Armenia (1 cm:2 km) published in 1932, the territory of the village of Kheyrimli was transferred to Soviet Armenia, although as in the case of the southern Armenian villages in the Borchaly district of the Georgian SSR (Akhkerpi, Chanakhchi, and Burdadzori), which were transferred to Armenia during the same period but later returned to Georgia, this decision was revised in Azerbaijan’s favour a few years later.

Map of the Armenian SSR in 1932 where the territory of the village of Kheyrimli is shown as part of Armenia. The red box marks the village of Kunen (the historical name of Kirants) and the border runs along the Voskepar river.

The complex and intersecting pattern of land-use and infrastructure in this area has continued. The Armenian population used the land and roads immediately around the village of Kheyrimli and even beyond it and it was only possible to get from the Azerbaijani pene-enclave of Askipara to the village of Kheyrimli by crossing Armenian territory. The village was located right on the line of the border with Armenia and the village cemetery was on the administrative territory of the Armenian SSR. The delimitation means that for the first time the border runs directly through the territory of the two villages which has already caused a lot of difficulties for the people of Kirants and will inevitably lead to similar issues (at least initially) for the returning inhabitants of Kheyrimli.

The third section (1.9 km) affected by the delimitation and demarcation process is between the villages of Berkaber and Gizilhajili. At first the delimitation in this area, in contrast to the previous two cases, didn’t meet with objections from the people of Berkaber. However, after the process was completed, there was a wave of protest. The key issue was the Azerbaijani military position to the north of the village of Gizilhajili (marked a on the map) which, according to reports from the residents of Berkaber, the Azerbaijani forces had not left. As a result, the Armenian border guards, who had left their base (d) but had another one near the Joghaz Reservoir dam (c), were unable to take up their duties.

White area – territory of Azerbaijan around the Armenian base which the Armenian armed forces left following the delimitation process.

Blue area – territory of Armenia (Berkaber ledge) still under the control of Azerbaijani armed forces.

Green line – section of the border in this area which is subject to delimitation in accordance with the map published by the office of the Deputy Prime Minister of Armenia on 19 April 2024.

By 15 May, when the commission’s final meeting on the ‘four villages’ was held, this issue had still not been resolved. Appeals from the Armenian media to the government remained unanswered. It was only during separate negotiations in June, after the process had been formally completed, that the two parties managed to find a solution. Recent satellite images obtained by journalist David Galstyan and information from the residents of Berkaber indicate that the Azerbaijani base (a) was moved further north, along the road between Ashaghi Askipara, Mazam and Qazax. Armenian border guards therefore now have unimpeded access to the whole area between Berkaber and Gizilhajili. This precedent may be seen as a local but important compromise, providing evidence of the capacity of the participants to find mutually acceptable solutions.

FUTURE PROSPECTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The situation around the return to Azerbaijani control of the four villages in the Qazax district was an important step in the Armenia-Azerbaijan peace process. To some extent it can be seen as a historic achievement which facilitated the resolution without bloodshed of at least part of the delineation issue on one of the most challenging sections of the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan. However, as mentioned above, this process was dominated by political motives rather than a logical or pragmatic approach. As a result, the pursuit of quick results at the expense of constructive compromise led to the adoption of an approach which was not the best tool for the job in this specific case, i.e. a strict adherence to the administrative border from the mid-1970s despite the fact that this was not consistent with actual land-use practice and settlement growth.

In fact, instead of establishing a precedent for settling border issues in a spirit of trust, the parties may now face a reality where delimitation and demarcation using this model becomes a source of new conflicts and resentment among the border communities of both countries.

Effective solutions to this issue involve, as a minimum, the possibility in certain cases of changing sections of the border during the delimitation phase. This means that the commissions of the two parties should be able to agree on a course for the line of the border on the map which is different from the 1976 version. In addition, determining a specific correction interval for the demarcation stage would allow the professional commissions to work out the best solution for a specific locality, based on established principles and permissible variations to the delimitation line.

It is worth noting that settlement growth, a lack of consistency between the administrative border and land-use practices on the ground, and the construction of reservoirs and communication lines were the main factors that led to the establishment of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border commission in the 1980s.

Under a return to the Soviet-era borders, the Azerbaijani village of Bala Jafarli on the southern shore of the Aghstafachay reservoir loses its link to the Azerbaijani ‘mainland’

The next step is to decide which section of the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan should be considered for the continuation of the delimitation process and whether there should be any changes to the principles and approaches adopted.

Ideally, the process would continue in Tavush, since in this region there are settlements on both sides of the border which have an interest in resolving the issues that have accumulated since the beginning of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan (Kamarli, Gaymagly, Mazam, Bala Jafarli, Yaradullu, Kohnagishlag, Mülkülü, Alibeyli, Aghdam and others on the Azerbaijani side and Berdavan, Barekamavan, Koti, Sevkar, Sarigyugh, Vazashen, Achajur, Kayan, Paravakar, Nerkin Karmiraghbyur, Movses, Aygepar and Chinari on the Armenian side). If the principle of rigid adherence to the Soviet-era border were to be applied here, the majority of the Azerbaijani villages along this part of the border would face similar or possibly even more intractable problems to those encountered by Kirants. The only similar situation is on the Goris and Kapan section, the difference being that the Azerbaijani villages there were abandoned between 1992 and 1994.

On all the other sections of the Armenian-Azerbaijani border the settlements are separated by ridges and natural barriers. Therefore a strict adherence to the administrative border which, as a rule, follows the watershed line of the ridges, shouldn’t present the parties with too many challenges. It is our view that the best approach would be to apply the principle of preserving communication lines, traditional land-use patterns and infrastructure (homes and other facilities) for all the villages adjacent to the border on both sides.

Accordingly, border sections could be divided into two different categories. There are the complex cases – Tavush, the Goris-Kapan and Yeraskh-Sadarak sections and the village of Khachik, as well as the territory of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic – where it would make sense to adopt the principles set out above. Then there are the other cases where the border follows ridges and other natural and artificial features, where a strict adherence to the 1976 border would be possible, thereby saving time and money on the delimitation and demarcation process.

An important issue in the Goris-Kapan section are the tongues of Armenian territory which protrude into and encroach on neighbouring territory, such as to the south of Nerkin Khndzoresk, to the east of Yeghvard and to the south of Agarak. These involve significant costs for both sides with respect to connectivity. An exchange on the principle of equal-sized areas of territory would thus be a reasonable solution. Generally speaking, using natural or artificial demarcations to find the best solution to border issues in the challenging sections is valuable for the purposes of reducing the cost of border security, as well as for economic activities and to facilitate communications and overcome other difficulties. This approach to the issue of exclaves (and territory exchange as the best route to resolving the complex problems associated with them) has been put forward repeatedly, including in our previous article on this topic.

Another example which is of interest is the current intensification of the delimitation and demarcation process between Armenia and Georgia. It includes appeals to the relevant EU bodies and individual countries, such as Lithuania, for assistance with producing new topographical maps that take account of changes on the ground. Inviting experts as consultants who can share their experiences and the solutions they have developed could be a useful tool to consider.

One matter which requires particular attention is how to deal with historic monuments which are located near the border and have symbolic and cultural significance for the two countries (the Armenian Khorakert monastery and the church in the village of Khojorni on the Georgian side of the border and the mediaeval Georgian monastery of Khuchapi on the Armenian side). There are similar monuments near the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan (including Azerbaijani village cemeteries, Armenian monasteries such as the Saint Sargis Monastery of Gag (Avey in Azerbaijani) and ruined churches) and in the border region between Azerbaijan and Georgia.

Finding common solutions to these problems and being able to establish criteria that are universal and take the interests of both sides into account is important for all the countries in the region. It is relevant to quote here Article 7 of the above-mentioned Agreement for the delineation of the borderline between the Republic of Macedonia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from 2001: “With regard to the cultural and historical monuments and memorials in the territory of both States, the Monastery St. Prohor Pcinski, the Serb military cemeteries and others, the contractual parties will conclude a special inter-State agreement that will determine the modalities of their renovation, maintenance and unimpeded access by the citizens of both countries”.

In addition to this, it would be useful to link the border delineation process between the countries of the region with work on an agreement on the trijunction of the borders of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan (the western heights of the Babakyar mountains) and to continue the delimitation process from this point in two directions – Armenia-Georgia and Armenia-Azerbaijan.

Another issue in this context is the shared use of water resources, particularly since the border area includes several reservoirs, the water from which was used jointly by the two republics during Soviet times (Joghaz, Aghstafachay, Khndzorut and others). It’s important to point out that the sources of almost all the rivers in the north-western part of Azerbaijan adjacent to Tavush and their catchments are located in Armenia. During Soviet times this practice of shared water use from reservoirs on the border was one of the reasons for the rapid development of border villages on both sides, for example around the Joghaz reservoir.

Another issue that has come to light during the ‘Tavush process’ is information policy around the activity of the commissions, with details of preliminary decisions appearing in the Armenian media and having an undesirable impact on the work of the negotiators. For the delimitation and demarcation work to be effective, there should be agreed statements from the commissions either in response to specific enquiries or at regular intervals. This issue needs to be resolved in order to ensure a positive reception of the process by the public in the two countries and to establish an atmosphere of constructive cooperation between the parties.

Samvel Meliksetyan

Translated from Russian by Heather Stacey. Read the original article in Russian here.