Azerbaijan and Armenia: Armed and Dangerous – Could military parity between Yerevan and Baku guarantee of peace?

This article, which was published on the website of the Baku Press Club, sets out the recent trends in military spending priorities in Armenia and Azerbaijan since 2020. At the end of a bloody three-year period it seemed as though the two adversaries would slow the tempo of militarisation and divert resources towards peaceful ends. But the reality is rather different. By essentially accepting the outcome of the war in 2020, Armenia signalled its intention to pursue a peaceful coexistence with Azerbaijan. However, it didn’t abandon its policy of acquiring new defensive weapons, regarding this as a guarantee of the country’s resilience. Meanwhile, Baku is also continuing to arm itself, concerned about possible retaliation from the Armenian side.

Where will these policies lead Baku and Yerevan? Can an arms race be a guarantee of peace or does it open a pathway to a new war?

The theory that the best guarantee of peace between Baku and Yerevan is military parity is popular in Armenia. At least, that’s the impression gained from reading statements by politicians, listening to speeches by experts and reviewing media reports and responses to them on social media. And this doesn’t just apply to the media in Armenia, it is mirrored in the Azerbaijani media as well.

How did the military potential of Armenia and Azerbaijan evolve during the years of conflict? What level had it reached just before the 44-day second Karabakh war and what is the direction of travel now? Which side is arming more intensively today? And, more generally, how realistic is it for military parity between Azerbaijan and Armenia to be reached in the foreseeable future? Has anyone thought about the consequences of raising these questions?

When two sides arm themselves, does that mean peace?

What if Armenia, with the help of new friends, is soon on a par with Azerbaijan in military terms and then the two states, armed to the teeth, realise it doesn’t make sense to leave this lethal equipment unused? If each side then responds accordingly, it will end in mutual destruction. It follows, then, that this situation means we will finally realise the inevitable logic of peaceful coexistence. Perhaps we will even agree to pursue a ‘parity’ of disarmament. Because maintaining that balance at the peak of military spending is too heavy a burden on young economies. Forming and maintaining a single flying squadron today costs more than maintaining an entire city or agricultural area.

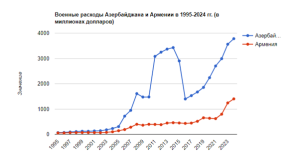

Interestingly, Azerbaijan and Armenia did have military parity at one time, but it didn’t help to solve their problems. Following the ceasefire in 1994, defence spending by the two countries remained evenly balanced for some years. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), this balance was noticeably beginning to break down by the end of the 1990s and by 2001 Azerbaijan had doubled the size of the gap in military potential between the two countries. In the early 2010s, this difference was 8.5 times. In 2014 Azerbaijan’s military spending reached a historic high: $3.43 billion against Armenia’s budget of $0.46 billion.

As a result, over the course of a quarter of a century and having spent more than $32 billion on military reform and rearmament, Azerbaijan had created a modern army ready for combat in new military operations. Meanwhile, Armenia’s defence spending during this period amounted to just over $7 billion.

We know how it ended in the fateful year of 2020.

Title: Military spending by Azerbaijan and Armenia, 1995-2020 (in $ millions)

Значение – Value

Blue – Azerbaijan

Red – Armenia

This graph shouldn’t immediately spark accusations levelled at the Armenian leadership that they begrudged their army funds and forgot about military parity with Azerbaijan. Paradoxically, throughout the 25 years, including 2020, Armenia was one of the most militarised countries in the world and, in percentage terms, allocated even more budgetary funds to the army than Azerbaijan. This is evidenced by the Global Militarisation Index (GMI), compiled by the Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies (BICC). The ranking in the table indicates the country’s place among 194 states globally, based on military spending as a percentage of national budget.

| Country/Year | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Armenia | 15 | 20 | 15 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Azerbaijan | 25 | 31 | 26 | 22 | 10 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 10 |

Since 1995, Armenia has tried to provide the army with the highest possible financial resources – as much as the budget allowed without completely denuding other areas. In terms of military spending as a proportion of state expenditure, Armenia has invariably been ahead of Azerbaijan and even reached second place in the list of the most militarised countries in the world. However, it is the starting point that’s important here. If the enemy is spending more on defence than your country’s overall budget, then nothing can be achieved by percentages. This was the case in the Caucasus in the early 2010s.

Pressklub.az has written about how the 2020 war between Azerbaijan and Armenia brought significant change ‘on the ground’, but surprisingly did not alter people’s attitudes. The spirit of confrontation was transferred from one plane to another, while the approaches to solving the problem remained largely the same. The conflict lives on in the minds of the people who are preoccupied with the same thoughts as they had before the war – to pump up their muscles, buy more weapons and acquire new military allies.

Incidentally, the ‘allies’ are quite content with this situation. In recent years, the global arms market has been developing at a furious pace. And who controls this market? The three Minsk Group ‘peacemakers’ – the US, France and Russia – who, even after the Group sank into a deep coma, privately retain their claims to the role of ‘mediator’ in resolving the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict. That’s how it is: arming with one hand and reconciling with the other. And they compete with each other, both in expanding their areas of military influence and in peacebuilding.

A break between wars: Azerbaijan

Today Armenia is seeking to end its dependence on Russia, including in terms of military supplies. This is happening at full volume and is accompanied by constant scandals. Azerbaijan travelled the same road seven or eight years ago, but without making a noise. By 2016-2020, Russia already only accounted for 16% of Baku’s military spending, compared to 79% in 2011-2015. In December 2016, at a joint press conference with the Israeli Prime Minister, President Aliyev for the first time announced a major military contract with Tel Aviv worth $4.85 billion and stated that most of the deliveries had already been completed. According to SIPRI, in the next five years Azerbaijan’s purchases represented 16% of all Israeli arms exports. Overall, its main military suppliers from 2016 until the second Karabakh war were Israel (68%), Russia (16%), Turkey (6%), Belarus (4.6%) and Slovakia (2.6%).

Thus, between 2011 and 2020, Azerbaijan became the largest arms importer in Europe and the 23rd largest in the world, acquiring 3.345 billion TIV worth of arms, according to SIPRI estimates. SIPRI uses a unique pricing system: the TIV measures the military capability transferred to the importer as a result of the transaction, rather than the financial value of the supplies. This creates a clearer picture of the power of the weapons acquired. During the same period, Armenia accumulated 398 million TIV.

After the war, Azerbaijan’s activity on the arms market reduced abruptly, but it soon began to pick up again just as sharply. In August 2021, Israeli and Azerbaijani newspapers reported another major arms contract worth $2 billion being prepared between the countries. Specialist publication ‘Defence Industry Europe’ revealed some details: part of the deal would involve the purchase of Barak MX air defence systems. These are mobile systems capable of defending against various types of missile, as well as planes, helicopters and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).

Some time later, the Washington-based Middle East Institute published an article saying that the Israeli corporations Meteor Aerospace and SpearUAV would deliver another batch of military equipment to Azerbaijan by 2024. SpearUAV is engaged in the development and production of UAVs, while Meteor Aerospace has been specialising in the development of missile systems, satellites and air defence systems for over 30 years. The Institute stated that Meteor Aerospace and the Caspian Ship Building Company (CSBC) had even established a joint venture in Baku to fulfil future contracts.

In December 2021, the Turkish Exporters’ Union (TİM) reported that Azerbaijan had become the second largest importer of Turkish-made military equipment, trailing only the United States. The Azerbaijani army now has more up-to-date UAVs in its arsenal than those used during the 44-day war – the Bayrakdar TB-3 and Akıncı drones.

At the same time, Azerbaijan is expanding the geography of its military suppliers, seeking to conclude new contracts primarily with European countries. In September 2021, a number of news agencies, referencing newspaper La Repubblica, reported that the defence departments of Italy and Azerbaijan were holding a technical round table to discuss “Italy’s contribution to the Azerbaijani armed forces modernisation plan” and that negotiations were underway “on the procurement of large-calibre weapons” worth up to $2 billion. And last year, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić said that his country had already signed a contract with Azerbaijan for the supply of self-propelled artillery units. According to media reports, the items concerned are 48 Nora B52 howitzers worth $339 million. They are designed to destroy artillery batteries and enemy bunkers and to open up passages in mined areas and are fitted with the latest equipment, including radar and sensors to simulate combat situations.

A break between wars: Armenia

Until the outbreak of the second Karabakh war, Armenia was firmly tied to Russia’s military-industrial complex, which technically supported its army. Yerevan received almost 94% of its weapons from Moscow between 2011 and 2020. The second more or less significant military supplier was Jordan (5.2%). However, the weapons Yerevan purchased from Amman also turned out to be Russian or rather Soviet-made. In autumn 2017, Jordan, which was modernising its armed forces, put up for sale 52 combat vehicles mounted with self-propelled Osa AKM surface-to-air missile systems. They were purchased through an intermediary by a company run by David Galstyan and transported to Armenia after repairs.

According to SIPRI, these deliveries (plus some ammunition from Ukraine) meant that Armenia ranked 67th in the world in terms of arms imports in 2011-2020, and over the course of ten years it fell behind Azerbaijan in the development of its military potential until Azerbaijan was nine times more powerful by this measure. Some sources say SIPRI did not take into account all elements of military-technical cooperation between Moscow and Yerevan, but this is no longer relevant, as the bulk of the equipment that the Armenian army received from Russia before 2021 was incapacitated during the 44-day war. The Azerbaijani side claims that the amount of Armenian weapons and equipment destroyed or captured in the war exceeded $5 billion.

Still reeling from the defeat, Armenia began to rebuild its army. According to SIPRI, in 2021, for the first time in the 21st century Armenia surpassed Azerbaijan in terms of activity on the arms market. By the end of the three post-war years (2021-2023), it ranked 77th (25 places above Azerbaijan) among the world’s arms importers. Its main military suppliers during this period were India (52%), Russia (42%) and France (5.6%).

Clearly, the Pashinyan government is on a quest for a new security system. Its basic principle, in the words of Armen Grigoryan, secretary of the country’s Security Council, can be formulated as follows:

“All our security guarantees were tied to Russia until at least December 2021. When Armenia found itself under threat, its allies simply did not come to its aid. Taking this into account, Armenia has started to diversify and look for new security guarantees.”

An important aspect of defence strategy is the choice of military partners. After the 44-day war, Armenia engaged in intensive negotiations with India. According to press reports, contracts worth more than $600 million were signed with Indian companies. New Delhi sold Yerevan two Akash mobile surface-to-air missile systems capable of engaging multiple targets simultaneously and later doubled their number.

Armenia also received from India Pinaka multiple rocket launchers, Konkurs anti-tank missile systems, 80 and 155 millimetre truck-mounted howitzers and Swathi mobile radars to detect and track sources of fire. Indian newspapers say that Armenia will soon receive a batch of ATAGS howitzers, which have proved themselves effective in mountain combat, worth another $150 million.

There are reports of an agreement between Yerevan and India’s Zen Technologies for the delivery of state-of-the-art ZADS anti-drone systems, which entered service just three years ago. ZADS disrupts the communication system of enemy UAVs and neutralises them. The parties recently signed an agreement to open a branch of Zen Technologies in Yerevan, which indicates big plans for the future.

At the same time, military cooperation between the defence departments of Armenia and France is growing rapidly. According to the agreement signed by their leaders, Paris will transfer to Yerevan three Ground Master 200 (GM200) radar systems from the Thales defence group. These are capable of quickly detecting and tracking different aircraft, including cruise missiles. The defence ministers also signed a memorandum of understanding on France’s intentions to supply Armenia with Mistral surface-to-air missile systems designed to hit low-flying objects.

In October 2023, in response to Azerbaijan’s warning that French weapons could trigger a new war in the region, the country’s Defence Minister Sebastien Lecornu said that Paris would continue to help modernise the Armenian military. During a repeat visit to Yerevan in February 2024, Lecornu reiterated that his country’s intentions were serious:

“We were talking about Mistral missiles. These are short-range missile devices. It’s quite easy to learn how to operate them and we’ve already had one discussion about this layer of defence. As a second layer, we will offer mid-level air defence. This is just about France’s capabilities in armament and training. There is also the question of production. As I said, there is a last layer defence too, which is a much more serious technology. In particular, we’re talking about Thales radars, and GM200 radars will be delivered in the near future.”

Yerevan, like Baku, is looking for opportunities to further expand the geography of its military suppliers. Armenia recently signed a military-technical cooperation agreement with Greece. And in early March 2024, Armenian Defence Minister Suren Papikyan held talks with the top leadership in Iran. “A number of agreements were reached on issues of mutual interest”, the Armenian Defence Ministry said following the visit.

Let’s arm ourselves for peace

All the data provided above on quantities and types of weapons are taken from open sources, although clearly this is not the most important information – that’s classified, a state secret.

But the available data is enough to provide a sense of the process through which the poisonous fruits of an unresolved conflict are ripening. We are in a high-tech arms race, which has been gaining unprecedented momentum since 2021. With severe delays in the conclusion of a treaty on the peaceful settlement of the issues that remain unresolved after two wars, the situation is becoming more and more menacing – communications remain blocked, tensions are rising over the fate of enclaves and the ownership of many areas of land in the border zone, and the diplomatic and information ‘wars’ are ongoing. Given the existence of an infinite number of risks, what other logical outcome could there be apart from a third war?

The trends observed in the evolution of relations between Armenia and Azerbaijan since 2020 suggest that Yerevan’s intensive arming with the aim of establishing military parity between the two states may in theory seem reasonable and pleasing to the ear of the one that was lagging behind. In practice, it looks unrealistic, at least in the coming decades and, in the words of Azerbaijani Minister of Foreign Affairs Jeyhun Bayramov, the prospect has an “inflammatory” ring to it.

| Year | Country | Military expenditure (in $ billions) | Growth compared to previous year | Budget share | GDP share |

| 2021 | Azerbaijan | 2.7 | 20.5% | 15.38% | 5.27% |

| Armenia | 0.619 | -2.4% | 15.58% | 4.47% | |

| 2022 | Azerbaijan | 2.99 | 11.1% | 14.92% | 4.55% |

| Armenia | 0.795 | 28.4% | 16% | 4.32% | |

| 2023 | Azerbaijan | 3.56 | 19% | 16% | 4.9% |

| Armenia | 1.24 | 47% | 19.4% | 5.6% | |

| 2024 | Azerbaijan | 3.78 | 6% | 17.4% | 5.4% |

| Armenia | 1.4 | 7% | 19.7% | 5.3% |

Money decides a lot in modern warfare. The table shows that Armenia is ahead of Azerbaijan in terms of both the growth rate of military spending and the level of militarisation of the budget. But all Armenia’s hopes of catching up with its neighbour fade away once the percentages are converted into dollars. From 2021 to 2023, Baku spent $9.25 billion on strengthening the army, while Yerevan spent $2.65 billion. Not only has there been no reduction in this imbalance, it has in fact grown by another $6.6 billion. Even at the current high level of military spending, it would take Yerevan five years to close the gap. And that’s without taking into account the $25 billion difference that developed before the second Karabakh war and assuming that Azerbaijan will freeze all defence spending. Whereas it doesn’t seem that Baku has such plans. Instead it is watching Yerevan’s actions very closely and is vigorously implementing countermeasures. The first graph showed the increasing distance between the two curves, demonstrating the growing difference in military power between Azerbaijan and Armenia in the 2010s. Let’s see how the situation has been changing in the 2020s.

Title: Military spending by Azerbaijan and Armenia, 1995-2024 (in $ millions)

Значение – Value

Blue – Azerbaijan

Red – Armenia

Azerbaijan is raising the bar higher and higher and this year it has allocated two and a half times (2.7 times to be precise) more money for defence than Yerevan, promising to maintain this superiority for many years. When this is the reality, how can Armenia achieve military parity which, according to a number of politicians and experts, is virtually the only “reliable guarantee” of lasting peace in the region? Or is there really a country somewhere in the world that is ready to provide Yerevan annually with the funds it lacks?

Military preparations have become the norm for us, such a habitual part of life that we have stopped thinking about the burden placed on our countries’ budgets by defence spending. The fact that, according to the latest data, Armenia ranks third in the world for militarisation while Azerbaijan ranks ninth is bad rather than good news for other areas of life in both countries. Armenia may have achieved an absolute record, increasing military spending by 47% in 2023 and raising it to $1.4 billion in 2024, but it only managed to allocate 60% of this amount from the budget to education, science, culture and sport combined. Meanwhile Azerbaijan reached a new peak, bringing military spending to almost $4 billion. Yet if we compare two items in the Azerbaijani budget – defence and social protection – we see a similar disproportion. Armenians and Azerbaijanis endured hardships, confident that peace would come and that they would then address their problems in areas such as education, health and pensions, but now it turns out that maintaining peace is more expensive than waging war.

Arif Aliyev

Turgut

Translated from Russian by Heather Stacey. Read the original article here.